The world of Chinese arts is vast, intricate, and deeply interwoven with the nation's historical, philosophical, and spiritual fabric. From ink painting to porcelain making, and from traditional music to calligraphy, every form of Chinese artistic expression holds a mirror to the country's ancient roots, dynastic transformations, and cultural symbolism.

This journey through Chinese arts is not merely an aesthetic one. It’s an immersion into a civilization that has thrived for thousands of years, expressing its identity, resilience, and worldview through strokes of a brush, the carving of jade, or the arrangement of silk threads.

Let’s dive into this remarkable realm that continues to inspire and evolve across the world.

Historical Foundation of Chinese Arts

The origins of Chinese arts trace back to prehistoric times. Archaeological discoveries, such as painted pottery and jade carvings from the Neolithic period, show that even early Chinese societies placed high importance on artistic expression. Over centuries, each dynasty added its own layer, developing unique styles and themes.

The Shang dynasty (1600–1046 BCE) marked a significant advancement in bronze casting, creating ritual vessels adorned with animal motifs and inscriptions. The Zhou dynasty brought refined jade carvings and decorative patterns that communicated authority and spiritual meaning.

During the Han dynasty, arts began to reflect Confucian values—balance, harmony, and respect for hierarchy. Meanwhile, Buddhist influences from India started shaping sculpture and mural painting, giving rise to spiritual depictions that would flourish under the Tang and Song dynasties.

The Yuan and Ming periods elevated porcelain to global acclaim, while the Qing dynasty emphasized delicacy and precision, producing detailed scroll paintings, cloisonné, and elaborate textiles. Each period didn’t just add art—it reshaped the way art represented human life, divinity, and the natural world.

Philosophical Roots and Symbolism

Chinese arts are deeply tied to philosophies such as Daoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism. These ideologies aren’t abstract background ideas—they actively inform artistic choices.

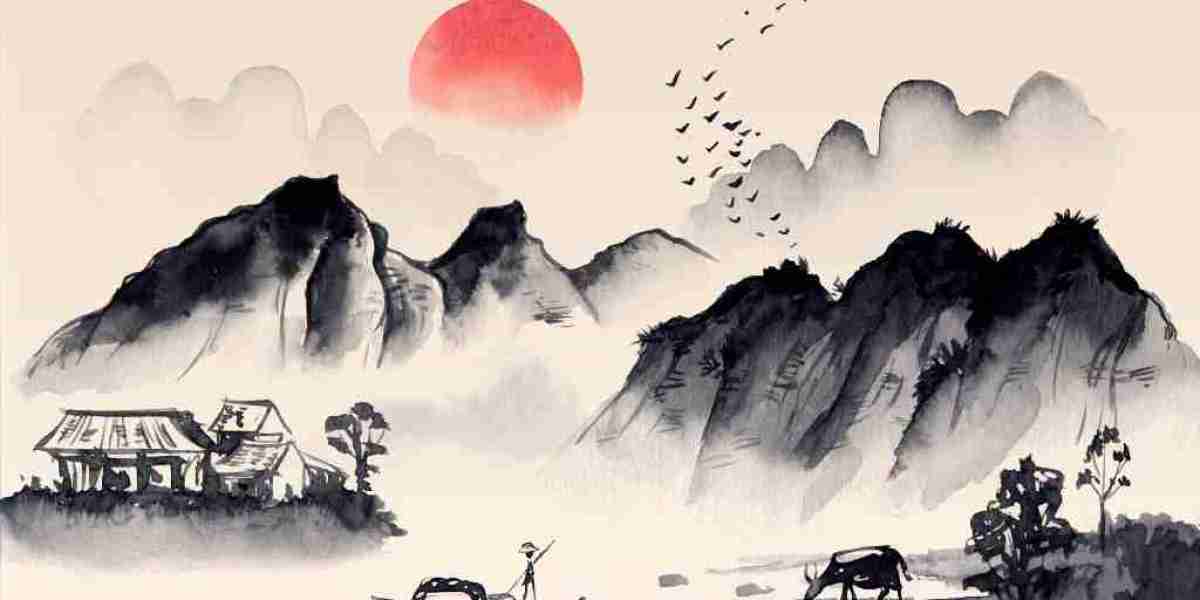

In Daoism, the belief in natural order and the flow of qi (energy) manifests in landscape paintings, where mountains, rivers, and mists seem to breathe and move. Artists strive to capture the spirit of nature rather than a realistic depiction. This approach is evident in shanshui (mountain-water) paintings, where emptiness is as expressive as detail.

Confucian ideals emphasize social harmony and moral virtue. These are reflected in ceremonial art, portraiture, and even architectural ornamentation, where elements are arranged to reflect balance and respect for structure.

Buddhist influence brought ethereal depictions of Bodhisattvas, mandalas, and heavenly realms, often rendered with gold and vivid pigments. The meditative quality of Buddhist-themed Chinese arts is meant to invoke peace and spiritual elevation, not just visual admiration.

In every piece, symbolism is key. A lotus represents purity, cranes signify longevity, and dragons embody power and authority. Understanding these symbols transforms the viewer from a spectator to a reader of visual poetry.

Calligraphy: The Soul of Chinese Arts

If painting is the heart of Chinese arts, calligraphy is its soul. Considered one of the highest forms of art, Chinese calligraphy transcends mere writing. Each stroke has rhythm, energy, and emotion. A skilled calligrapher isn't simply writing words—they're performing an expression of spirit and thought.

Tools such as the brush, ink stick, inkstone, and paper are referred to as the “Four Treasures of the Study.” Calligraphers train for years to master the delicate control needed to form characters that are both technically correct and emotionally powerful.

Styles vary from the disciplined regular script to the free-flowing cursive script. Historical figures like Wang Xizhi and Su Shi are revered not only for their literary work but for their calligraphic legacy.

Today, calligraphy remains a respected discipline, taught in schools and practiced by artists across generations. It continues to bridge language, art, and personal expression in a way few mediums can match.

Chinese Painting: Beyond the Canvas

Unlike Western art, where oil and realism dominate, Chinese arts take a different approach to painting. Ink and brush on rice paper or silk create works that focus on essence rather than detail. Subjects are often symbolic—bamboo for integrity, plum blossoms for resilience, and fish for abundance.

Scroll paintings, both hanging and handscrolls, are popular formats. These are not just visual displays but narrative journeys. A viewer “reads” the painting from one end to the other, discovering new elements and meanings as they go.

The practice of literati painting is especially notable. Scholar-artists combined poetry, painting, and calligraphy in a single composition, crafting pieces that were deeply personal and intellectual. These paintings weren’t made for commerce—they were statements of inner thought and scholarly identity.

Modern Chinese painters blend these traditions with contemporary techniques, creating an evolving art form that honors the past while speaking to the present.

Music and Performing Arts

The musical side of Chinese arts is equally rich. Traditional instruments like the guqin, pipa, erhu, and dizi have been used for centuries to convey emotion, tell stories, and accompany rituals.

The guqin, a seven-stringed zither, was particularly revered by scholars and sages. Its music is meditative and introspective, requiring both technical skill and spiritual focus.

Chinese opera, such as Peking Opera and Kunqu Opera, combines music, drama, martial arts, and acrobatics. It is a complete sensory experience, with stylized gestures, elaborate costumes, and symbolic makeup colors that reveal a character’s personality and fate.

Dance and martial arts also form part of the broader tapestry. From court dances of the Tang dynasty to modern choreographed performances, movement in Chinese culture is often rhythmic, expressive, and connected to spiritual or philosophical meaning.

Traditional Crafts and Decorative Arts

Craftsmanship is central to Chinese arts. Whether it’s silk weaving, paper cutting, or porcelain design, the emphasis is always on mastery and detail.

Porcelain, known worldwide as “china,” was perfected during the Ming dynasty. The blue-and-white porcelain designs remain iconic today, cherished for their elegance and durability. Cloisonné enamelwork, lacquerware, and jade carving are other refined arts that speak to China’s technical ingenuity and aesthetic discipline.

Chinese embroidery, often used in garments and home decor, is a painstaking art form where threads form detailed patterns of flowers, animals, and mythological creatures. Each region has its unique style—Suzhou embroidery, for instance, is known for its double-sided technique and lifelike imagery.

Even in architecture, decorative elements abound. Roof figures, window lattices, and garden rock arrangements are all infused with symbolic purpose. They’re not just functional—they communicate beliefs, aspirations, and cosmological ideas.

Influence of Chinese Arts Globally

The appeal of Chinese arts is not confined to the borders of China. Across Asia, Europe, and the Americas, its influence can be seen in painting, fashion, design, and even cinema.

Museums around the world host Chinese art collections that attract millions of visitors annually. Universities offer courses on Chinese aesthetics, and collectors seek antique scrolls, ceramics, and artifacts for both their beauty and historical value.

Modern Chinese artists are also making waves internationally. By blending tradition with contemporary perspectives, they’re redefining what Chinese art can be in the 21st century.

Festivals like the Chinese New Year showcase traditional performances, lantern art, and dragon dances—bringing the joy and creativity of Chinese culture to audiences worldwide.

Online platforms now make it easier than ever to explore and purchase art inspired by or directly sourced from Chinese artisans. Whether it’s a hand-painted silk fan or a modern reinterpretation of ink landscapes, these pieces continue to tell stories that transcend time and geography.

Final Thoughts

Chinese arts offer far more than visual enjoyment—they provide a gateway to understanding a civilization’s philosophy, history, and way of life. They capture what words often cannot: the flow of a river, the strength of a bamboo stalk in the wind, the calm of a meditative heart.

Engaging with Chinese art is not just a matter of cultural curiosity—it’s a journey into the soul of one of the world’s oldest and most complex cultures. Whether you’re admiring a Ming vase, listening to the gentle tones of a guqin, or watching a painter bring life to a blank scroll, you’re witnessing something timeless.

And perhaps, as you reflect on these expressions, you’ll realize the answer to the tricky question: to truly understand Chinese arts, you must look beyond the surface and step into a world where every stroke, color, and note tells a deeper story.